'Museum' on West Valerio

Renovated Home is a Blast from the Past

Address: 230 West Valerio Street

Originally Published in The Santa Barbara Independent

Link to original article here: https://www.independent.com/2021/10/21/museum-on-west-valerio/

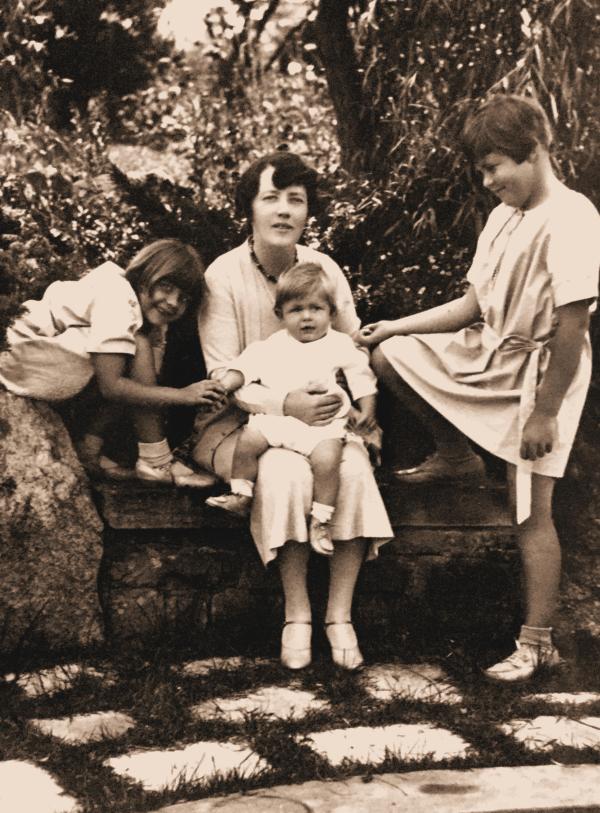

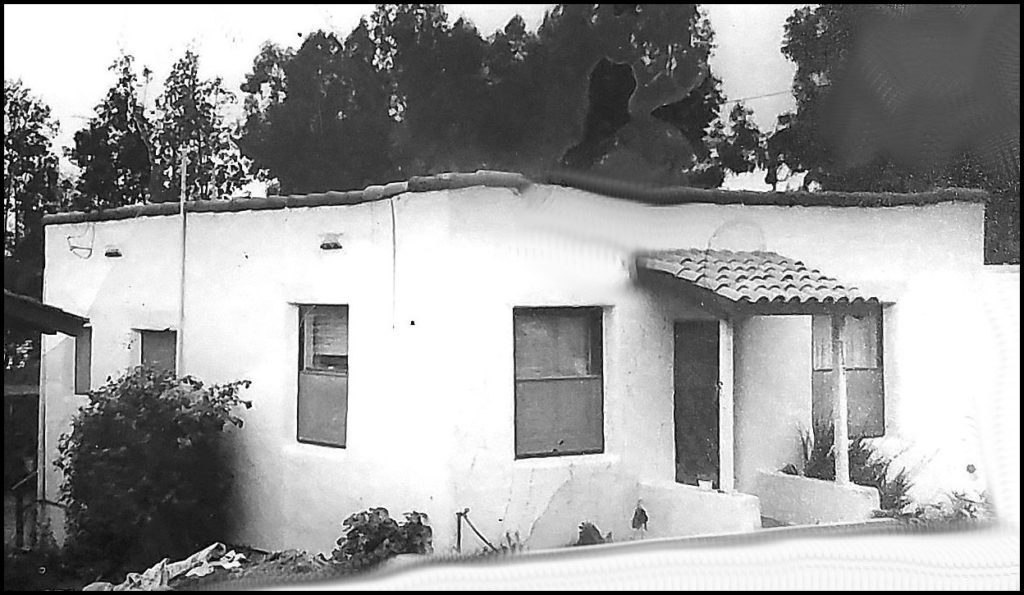

Only a dozen or so homes in Santa Barbara have been featured in Old House Journal magazine. This is one of them. Walking into the home is like walking back in time. The furniture and décor echo the Craftsman bungalow style that was popular a century ago. This home was built in 1912 for $1,500. The owners, Robert Sponsel and Patricia Chidlaw, joke that some of their renovations cost more than that. They call the home “our museum.”

The home’s exterior colors and plantings blend smoothly with the style. A 1914 paint catalog noted, “The bungalow is distinctively a suburban house … to make it attractive, the colors as well as the architecture must harmonize with nature.” The risers on the front steps are decorated with a vine called creeping fig (Ficus pumila) that also grows on the famous Gamble House in Pasadena.

One of the most eye-catching items in the kitchen is a 1930s GE refrigerator. These appliances were commonly nicknamed “monitor” refrigerators because the round compressor on top resembled the gun turret on the USS Monitor, an ironclad Civil War vessel.

Credit: Betsy J. Green

Good News, Bad News

Imagine picking up the morning paper and reading your own obituary! That’s what happened to E.J. Peterson, the home’s first owner. The obit used his name but described the life and death of another S.B. resident named E.J. Hayward, a well-known photographer.

I suppose that the good news about reading his own obituary notice is that he was able to contact the paper and get a correction printed the next day. The paper called it “an unfortunate mix-up,” and added that “Mr. Peterson … is very much alive and the mix-up in names kept Mr. Peterson denying that he was even ill.”

One of the home’s most interesting owners was Henry Augustus Adrian and his wife, Phila, who owned the home in the early 1920s. Adrian had served as the superintendent of schools and was the mayor of Santa Barbara in 1926 and 1927. In addition to these careers, Adrian often traveled the country as a speaker in Chautauqua assemblies. The Chautauquas were a sort of continuing education for adults that traveled from town to town. The practice began in Chautauqua (chuh-TAW-kwah), New York, in 1874. Generally, the group would set up a tent in a town and present a weeklong series of educational lectures and performances. Adrian was a friend of the botanist Luther Burbank and spoke about his plant research.

Another interesting owner was F.H. Kimball and his wife, Charlotte. Kimball was the president of the Veronica Medicinal Springs Water Company. This was a mineral spring located near Veronica Springs and Las Positas roads.

Hard Work and Luck

Here’s another example of good news and bad. When the present owners bought the house in 1980, it had been “modernized” in the 1960s by an owner who painted the woodwork white and ripped out the original cabinets. The good news was that he had taken “before and after” photos, which enabled Robert and Patricia to restore their home to its original appearance.

Apart from stripping paint, they had some lucky finds in their search for period-appropriate fixtures. Patricia happened to be walking the dog one day and found a beautiful claw-foot bathtub that had been discarded. Salvaged items from nearby demolitions also helped keep down the restoration costs.

What advice do they have for homeowners wishing to attempt similar retro decorating? “Bob and I were fortunate that we started looking in the early ’80s before the vogue for restoring Craftsman homes. You could still find inexpensive pieces in thrift stores and at yard sales. I guess my advice would be to study the books and familiarize oneself with the style and then look at resale situations and hope to get lucky. The Stickley furniture company is still in business and making beautiful reproductions of classic designs. While these are not cheap, I imagine they could be considered a good buy because the solid oak will certainly last more than a lifetime.”

Please do not disturb the residents of 230 West Valerio Street.